Rational Choice for Christmas

American media recently brimmed with venomous headlines cursing disobedient Americans who met their loved ones for Thanksgiving despite the CDC’s  COVID warnings. “As Americans prepare to gather for Thanksgiving, the world watches with dread and disbelief,” said the Washington Post in a revealing specimen of the genre.

COVID warnings. “As Americans prepare to gather for Thanksgiving, the world watches with dread and disbelief,” said the Washington Post in a revealing specimen of the genre.

One shudders awake from the customary lethargy and despair induced by the pages of the Washington Post. Perhaps the paper had run opinion polls to discover if representative humans – Kenyan cattle herders, say, or Iraqi pilgrims – know the first thing about Thanksgiving? Are ordinary folk out there on the dusty plains and crowded streets of the Third World resignedly shaking their heads at American recklessness?

No. Just the opposite.

By “the world,” the Post meant only a handful of foreign disease experts and media types it had dug up to reiterate its own hardline pro-lockdown opinions. That shows one way to disguise a strident opinion piece as a simple news story. “A mindbogglingly dangerous chapter in the out-of-control American COVID-19 story,” says a virologist from Queensland, an Australian state famous more for beaches than scientists.

But, as we hunker down for the coming second wave of bitter media abuse directed at Christmas, consider two facts that the Washington Post omits. First, the evidence for the efficacy of lockdowns is weak to non-existent. Second, every action on COVID, as in life, is a trade-off between costs and benefits. Americans weigh the individual and social benefits of Thanksgiving and Christmas against the risks of more COVID. Many come down on the side of the celebration. In this, they're not too different from people elsewhere, who are also continuing to celebrate the festivals and traditions of their tribes and communities, even at some more risk of COVID. And that's, arguably, a rational choice.

Let’s stipulate that the caste of experts, managers, media propagandists, and “influencers” is not necessarily wrong; locking down Thanksgiving and Christmas could help slow the pandemic. But they are not necessarily right either. There is little systematic statistical evidence that differences in lockdown policies have affected the COVID-19 pandemic at all.

_medium.png) Lacking a well-supported model of the forces driving the pandemic, experts also fail to predict its twists and turns over time. (Figure). The current second wave has hit Europe’s COVID death rate harder than the U.S. so far, despite the continent’s supposedly more effective pandemic policies. Brazil, widely abused for its failure to lockdown, now has a death rate much lower than either Europe or the U.S. I don’t recall experts predicting much of that three months ago.

Lacking a well-supported model of the forces driving the pandemic, experts also fail to predict its twists and turns over time. (Figure). The current second wave has hit Europe’s COVID death rate harder than the U.S. so far, despite the continent’s supposedly more effective pandemic policies. Brazil, widely abused for its failure to lockdown, now has a death rate much lower than either Europe or the U.S. I don’t recall experts predicting much of that three months ago.

To blame the experts is to miss the point, though. The epidemiology of pandemics is as soft science as economics or climatology. It is lousy at predictions because pandemics, like the macroeconomy and the climate, are incredibly complicated. Thus it’s hard to blame Dr. Fauci for his inevitable mistakes and flip-flops, though you should fault him for claiming to know more than he does.

Our managerial-expert class not only knows less than it claims; its approach to COVID policy is despotic in spirit. It mostly rejects trade-offs between costs and benefits, compromise or balancing one set of interests against another.

In an earlier post, I noted that in its 2017 pre-pandemic guidelines, the CDC had insisted on the need to balance social and economic costs against the public health benefits of pandemic actions. Yet, in an extraordinary political coup that historians will study for decades, an ad-hoc alliance of state governors, politicized federal health bureaucrats, and media fiercely championed and rammed through a hodge-podge of lockdowns without any backing in earlier guidance or analysis of trade-offs. All under a banner of “Follow the Science,” to be sure.

And yet, the costs of lockdowns are likely to be high and varied, coming on top of the effects of the spontaneous social distancing people undertake to avoid infection. They include loss of incomes and livelihoods, especially among the poor, worsening inequality, long-term damage to children from disrupted schooling, and harm to psychological and physical wellbeing from isolation and delayed medical screenings and procedures. There is also long-term erosion of civil liberties, the rule of law, and democracy due to the emergency COVID powers taken on by governments.

The costs could be more pervasive yet. Independence Day, Thanksgiving, Christmas are not only sources of personal happiness for the families and friends who meet to celebrate them. They are affirmations, renewals of the common sentiments, loyalties, and aspirations that bind together and build trust among far broader communities up to the nation. Democratic self-government is not possible without a pre-political “first-person plural,” a sense of the “we” who, despite our political differences, recognize and trust each other as members of a family in a shared home, fellow citizens. There is also lots of evidence for the importance of trust for economic development and prosperity.

The Washington Post denounces Thanksgiving travelers who, while they may knowingly accept more COVID risk for themselves, also impose it on innocent others. That is the economist’s notion of an “externality.” But some Thanksgiving externalities cut the other way. While you’re having a ball with cousin Javi and Aunt Meg, you’re probably not accounting for your contribution to sustaining the institution of Thanksgiving and the valuable social capital that it embodies. I’m not sure how the social cost-benefit calculus of Thanksgiving 2020 will add up, looked at a few decades in the future.

For the moment, though, people worldwide continue to celebrate their vital traditions.

In September, for example, thousands of Maasai gathered in the Maparasha Hills of Kenya for the once-in-15-year Olng’esherr ceremony when the Moran (warrior) age group graduate to Mzee (elders). In this age-based traditional social system widespread in Africa, males are divided into age sets with the same social and political duties. Age sets ceremonially graduate to the next higher at fixed times, taking on new and higher responsibilities in the community. John Reader says in “Africa: A Biography of the Continent” that the system discourages the emergence of powerful hereditary chiefs or families, spreading power and authority horizontally throughout the group, touching every lineage and family.

The Kenyan government has banned meetings of over 100 people but wisely  accommodated the Maasai’s need to hold Olng’esherr this year, despite the risk of more COVID. “We’ve heard about corona but I think God is in control,” says a Maasai moran in the accompanying BBC video

accommodated the Maasai’s need to hold Olng’esherr this year, despite the risk of more COVID. “We’ve heard about corona but I think God is in control,” says a Maasai moran in the accompanying BBC video

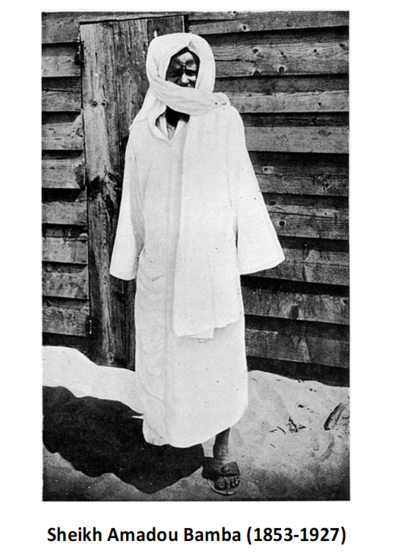

In October, thousands of Iraqis gathered at the shrine of Imam Hussein in Karbala for Arbaeen, the annual commemoration of the Imam’s martyrdom at the Battle of Karbala, 680 CE. Also in October, according to the New York Times, “huge throngs of people” traveled to the city of Touba in Senegal for the Magal, West Africa’s largest religious festival. Magal draws four or five million people in a typical year. It commemorates the 1895 exile of Sheikh Amadou Bamba, who founded the Mouride Sufi brotherhood and led a peaceful struggle against the French colonial authorities.

_medium.png) Yet, despite these vast gatherings, COVID death and infection rates in Kenya, Iraq, and Senegal remain far below those in Europe or the United States, or even Brazil. (Figure.)

Yet, despite these vast gatherings, COVID death and infection rates in Kenya, Iraq, and Senegal remain far below those in Europe or the United States, or even Brazil. (Figure.)

[Language edits December 9 2020.]